Journal

From words to deeds

On Finland’s Day of Equality, it’s important to hear a variety of voices and perspectives. For people with disabilities, Finland is still far from being a model country for equality.

“I couldn’t care less what people say!” This famous quote is attributed to the pioneering Finnish author Minna Canth (1844–1897). It continues to inspire feminists and human rights defenders to this day. A fearless attitude is admirable — and often essential — in human rights work.

But the world is, unfortunately, nowhere near ready. A disability activist may not receive the support they need to even leave their home, let alone join a demonstration, especially when public transport is inaccessible. And if they do manage to get out, they may be met with angry shouts or constant staring from passers-by.

As members of a minority, we are simply not in a position to be completely indifferent to what others say or do. But this reality must not silence us. On the contrary, we must raise our voices even louder. That’s what Judith Heumann (1947–2023) did — an activist and changemaker I deeply admire, who passed away in early March. I believe Minna Canth would have done the same. In her writing, she often stood up for those in vulnerable positions and exposed society’s twisted attitudes with skill and precision.

Not all of us will become world-shapers like Judith or Minna. But each of us can try to do our part. Minna Canth’s house, Kanttila in Kuopio, is currently being renovated for future cultural use — with accessibility, I understand, being taken into account. I hope that everyone who wishes to visit will be able to do so once the renovation is complete.

Demanding rights

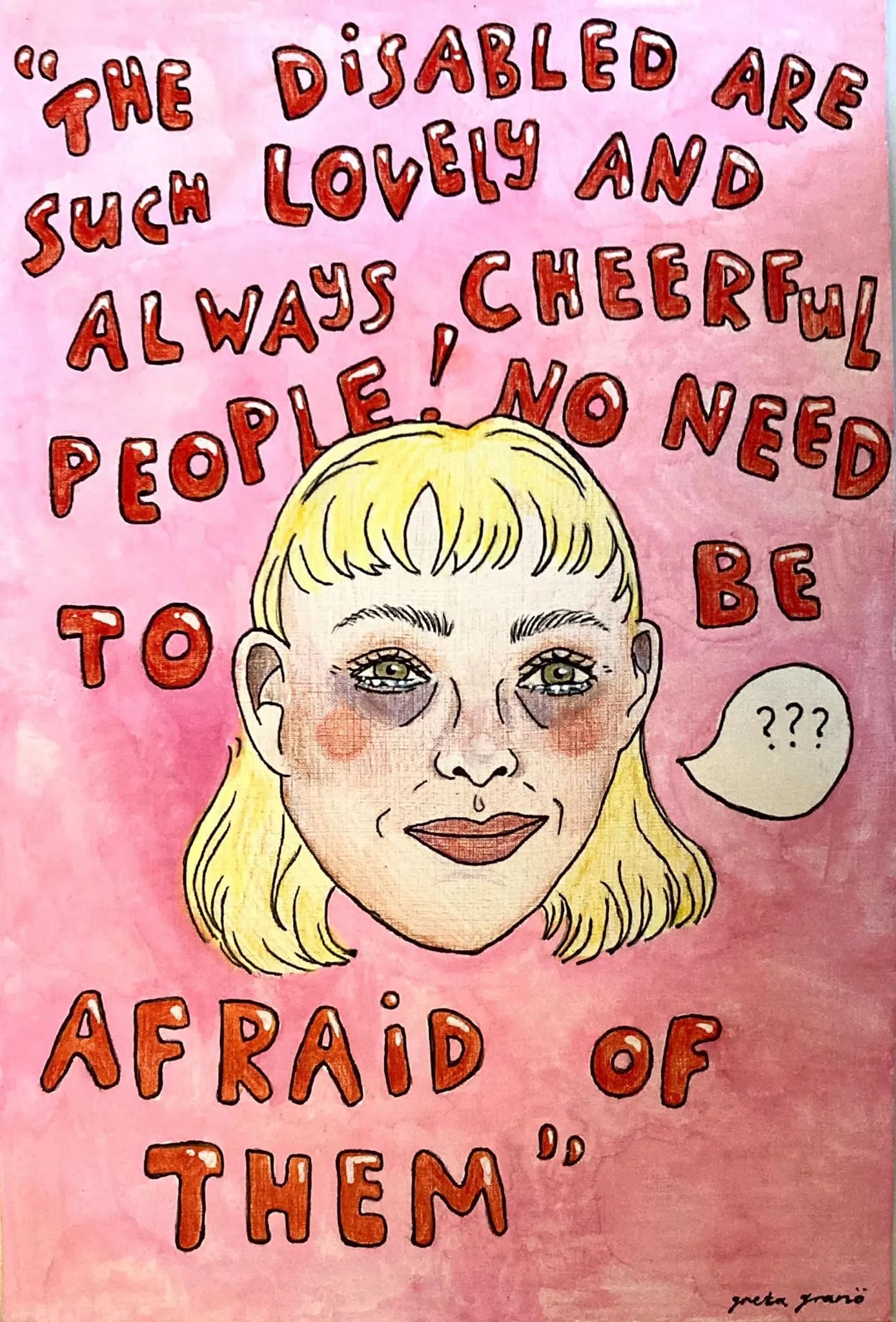

So, is Finland not a model of equality after all? Aren’t things pretty good here for people with disabilities? Am I not grateful for what I have? Aren’t disabled people generally cheerful and sweet? Many might think I’m complaining for no reason. Some may even find it irritating.

Of course, I can’t speak for anyone else with a disability. But to those wondering: yes, I’m aware of my privileged position. I have a spouse, family, and friends. I’ve had access to education and employment. My voice is heard, and I’m even paid to express my views publicly. I was raised by strong women. The long tradition of equality work in Finland has benefited me, too. Compared to many places in the world, my situation as a disabled person is far from terrible.

Still, my personal good fortune doesn’t mean there’s nothing to fix. I regularly face prejudice and have to explain why I need services that allow me to participate in society, like being able to work. I don’t mind, because I’m in a position to advocate for myself.

But many disabled people in Finland are in a weaker position, and their strength may be running low. In my work at a human rights organization, this truth is impossible to ignore. Outside of work, it often leads to awkward silence. At worst, it means being left behind in institutions or assisted living units that, due to understaffing, increasingly resemble institutions. Out of sight, out of mind — and no wonder people with disabilities aren’t always visible in public spaces.

Another issue that has come up in recent years is the question of who has the right to intensive care when seriously ill. These discussions are often dominated by non-disabled experts. A few headlines may be written about the most extreme cases, and then life goes on as usual. The expertise of disabled professionals—do they even exist?—is rarely utilized, and the voices of disabled people themselves are often left unheard.

“Words are also acts of power—they can hurt or aim to do good. That’s why I use my own words and the space given to them in the spirit of Minna Canth, equality, and justice.”

Settling for Less Is Not Enough

The public conversation about disability in Finland is strangely lacking in ambition and analytical depth. We still have a long way to go from being objects of care to becoming full citizens. Disability is often seen not as part of humanity, but as a problem to be solved with a one-size-fits-all approach. Once a minimum level of well-being is reached, we’re not supposed to hope for more — or at least not say it out loud. I doubt Minna Canth would have had much patience for this hush-up mentality.

I still can’t claim I don’t care what people say. I’m not above worrying about how others perceive what I say or write. But society won’t improve by settling for the benefits gained by a few or by staying silent. Words are deeds. Words have power. They can hurt or heal. That’s why I use mine — and the space I’ve been given — in the spirit of Minna Canth, equality, and justice.

Image: Greta Granö. Kalevala x Vammaiset tytöt art camp, autumn 2022.

On Minna Canth Day, which also marks Finland’s Day of Equality, we give the floor to Sanni Purhonen, journalist, information officer at the human rights organization Kynnys ry, creative writing teacher, and poet. She has published three poetry collections, among other works, and is active in the women’s network of disability organizations. Kalevala Jewelry collaborates with Rusetti ry, the national association for women with disabilities. We have funded the creation of the online media platform for girls with disabilities at vammaisettytöt.fi.

Blog author: Sanni Purhonen, journalist, publicist, creative writing teacher and poet

Three powerful voices on minority rights

Kalevala Jewelry works in partnership with Rusetti ry. Our goal is to make girls and young women with disabilities visible in society.

The article Three powerful voices sheds light on the everyday lives of minorities. One of the contributors is Anni Täckman, project manager at Rusetti ry: "We call it the garden gnome syndrome: disabled women are often seen as a colorless, tasteless, genderless mass — not even as sexual beings. It’s about society’s attitudes and prejudices toward disabled people.”

Read how the world looks through the eyes of young women with disabilities.